In 2021, declaring NFTs as "funny pictures" and a surefire way to earn was unwise; in 2024, considering NFTs as a bygone era seems equally shortsighted. In a short period, we've witnessed a full life cycle of this digital asset class — from emergence and speculation to temporary decline. "Temporary" is key here, as NFTs continue to exist, evolve, and are certain to reappear, under the same or a new guise.

Will we be ready for their return? Yes, if we understand the reasons behind the successes and failures of NFTs in their first iteration.

Will we be ready for their return? Yes, if we understand the reasons behind the successes and failures of NFTs in their first iteration.

I. HISTORICAL CONTEXT

To understand NFTs, it's essential to consider their origins, so let's delve briefly into digital art history. Some might cite László Moholy-Nagy's 1920s experiments, where he dictated tasks to apprentices by phone, as precursors to digital art. Others might go further back to Albrecht Dürer’s use of the printing press for lithographs, seeing a union of art and technology there. Our starting point is the mid-1960s — the early development of algorithms for generative art, i.e., computer-generated art based on human-programmed algorithms.

Mass attention to digital art, with attempts to situate it in art history, emerged in the next decade with the "Demoscene." Here’s a chronological outline of subsequent digital art directions:

Mass attention to digital art, with attempts to situate it in art history, emerged in the next decade with the "Demoscene." Here’s a chronological outline of subsequent digital art directions:

- 1970–1985: Demoscene

- 1990–2000: Computer Art

- 2015–2016: Crypto Art

- 2017: Blockchain Art

- 2018: Digital Art

Not everyone accepted "digital art." Several marketplace lawyers proposed a legal term to classify blockchain art as a separate asset class, exempt from traditional investment classifications. They argued that each piece of art is unique (unlike stocks), making art investments distinct from typical financial assets. Regulators, unfamiliar with art investment norms, granted NFTs a special status.

Thus, the term "non-fungible token" was born.

II. NFTS: A THEORETICAL OVERVIEW

Over recent years, many definitions and comparisons have emerged to simplify understanding NFTs. Here’s ours: imagine you buy a painting at an auction — a traditional canvas piece in a lovely frame. The purchase comes with an addition: a pocket attached to the back, containing all the accompanying documents — provenance, artist biography, expert evaluations, sales contract, and ownership proof. In short, everything that rarely accompanies a sale in full.

This pocket is regularly updated with news about the artist, price indices, exhibition invitations, and more. A "magic button" also lets you instantly resell the artwork at a set price. Essentially, the collector has an automated management system included with the artwork!

This is the NFT format’s theoretical foundation. An NFT is a digital algorithm combining the asset, sales contract, and ownership rights into one computer code.

In the art world, NFTs were theoretically expected to fulfill several responsibilities:

NFT algorithms were designed specifically for digital assets, meaning that this integration of work and documentation in code applied exclusively to artworks created in digital form. Yet, some innovators attempted to "fit" physical artworks into NFTs (more on this in the next section). It turned out, however, that no legal connection existed between a physical asset and its digital certificate, as legislators had not yet established one.

This pocket is regularly updated with news about the artist, price indices, exhibition invitations, and more. A "magic button" also lets you instantly resell the artwork at a set price. Essentially, the collector has an automated management system included with the artwork!

This is the NFT format’s theoretical foundation. An NFT is a digital algorithm combining the asset, sales contract, and ownership rights into one computer code.

In the art world, NFTs were theoretically expected to fulfill several responsibilities:

- Authenticity Verification: Since all works were initially registered in a blockchain system, the system could automatically present the needed certificate upon request.

- Originality: The algorithm could check a work for "resemblance to the point of confusion" and identify stylistic borrowings, themes, or outright duplicates.

- Uniqueness: Blockchain entries setting edition limits prevented the creation of copies beyond the original artist’s specified number.

- Liquidity: NFT algorithms monitored the market, notifying collectors when their asset was requested for purchase and assessing the adequacy of the offered price.

NFT algorithms were designed specifically for digital assets, meaning that this integration of work and documentation in code applied exclusively to artworks created in digital form. Yet, some innovators attempted to "fit" physical artworks into NFTs (more on this in the next section). It turned out, however, that no legal connection existed between a physical asset and its digital certificate, as legislators had not yet established one.

By 2020, the traditional art market was a 300-year-old system with auctions, galleries, fairs, museums, indexes, and 150 years of public sale statistics. The "pockets" of digital art collectors, however, had little to fill them: no digital museums, biennales, or substantial statistics existed. Only a handful of online marketplaces, a few European galleries, and one American art fair operated consistently.

From the promised system of managing artworks, only a few NFT features functioned fully: the ability to buy and sell quickly and to automatically allocate royalties to artists (5%–30%) with each resale. This appealed to two main groups: speculators, who saw a new high-liquidity market, and artists, who saw an opportunity for unprecedented earnings.

When the NFT concept officially launched in spring 2018, it initially gained little traction; the crypto market was in a downturn, and marketplaces barely survived with small user bases propped up by constant "giveaways" and encouraging social media engagement. For the next two years, the digital art asset market was like a suitcase without a handle: cumbersome to carry but hard to abandon. Still, platforms that had received development investments in 2017–2018 remained optimistic, buoyed by faith in decentralization and reliable salaries, secretly hoping for a cryptocurrency market rebound... or a miracle.

When the NFT concept officially launched in spring 2018, it initially gained little traction; the crypto market was in a downturn, and marketplaces barely survived with small user bases propped up by constant "giveaways" and encouraging social media engagement. For the next two years, the digital art asset market was like a suitcase without a handle: cumbersome to carry but hard to abandon. Still, platforms that had received development investments in 2017–2018 remained optimistic, buoyed by faith in decentralization and reliable salaries, secretly hoping for a cryptocurrency market rebound... or a miracle.

III. THE NFT BOOM

Observing events from 2024, it’s easy to identify the factors that triggered the NFT boom. However, it’s crucial to recognize this: from its inception to global fame, the NFT technology lay virtually untouched for nearly three years! What helped it "wake up famous" one day?

- A New Cycle of Cryptocurrency Capitalization Growth

- Centralized Holdings of Large NFT Collections by a Few Hundred Owners

- Generation Z’s Rejection of Parents’ Collecting Values

- Ethereum’s Ambition to Challenge Bitcoin

- A Collective Effort by Key Players

These factors set the stage for NFTs, but even they wouldn't have succeeded without a receptive market. By 2021, the "creative" economy (art, fashion, music, film, gaming, etc.) was worth $2.3 trillion, while the crypto economy was valued at $2.2 trillion, with each boasting millions of participants and exponential online sales growth.

Together, these markets created a digital art “earthquake,” followed by a wave of euphoria. NFTs were rapidly labeled "art," akin to calling a museum ticket “art” for the experience it facilitates. Serious publications began classifying NFT art as a distinct field, parallel to (not part of) digital art, capturing the imaginations of young collectors.

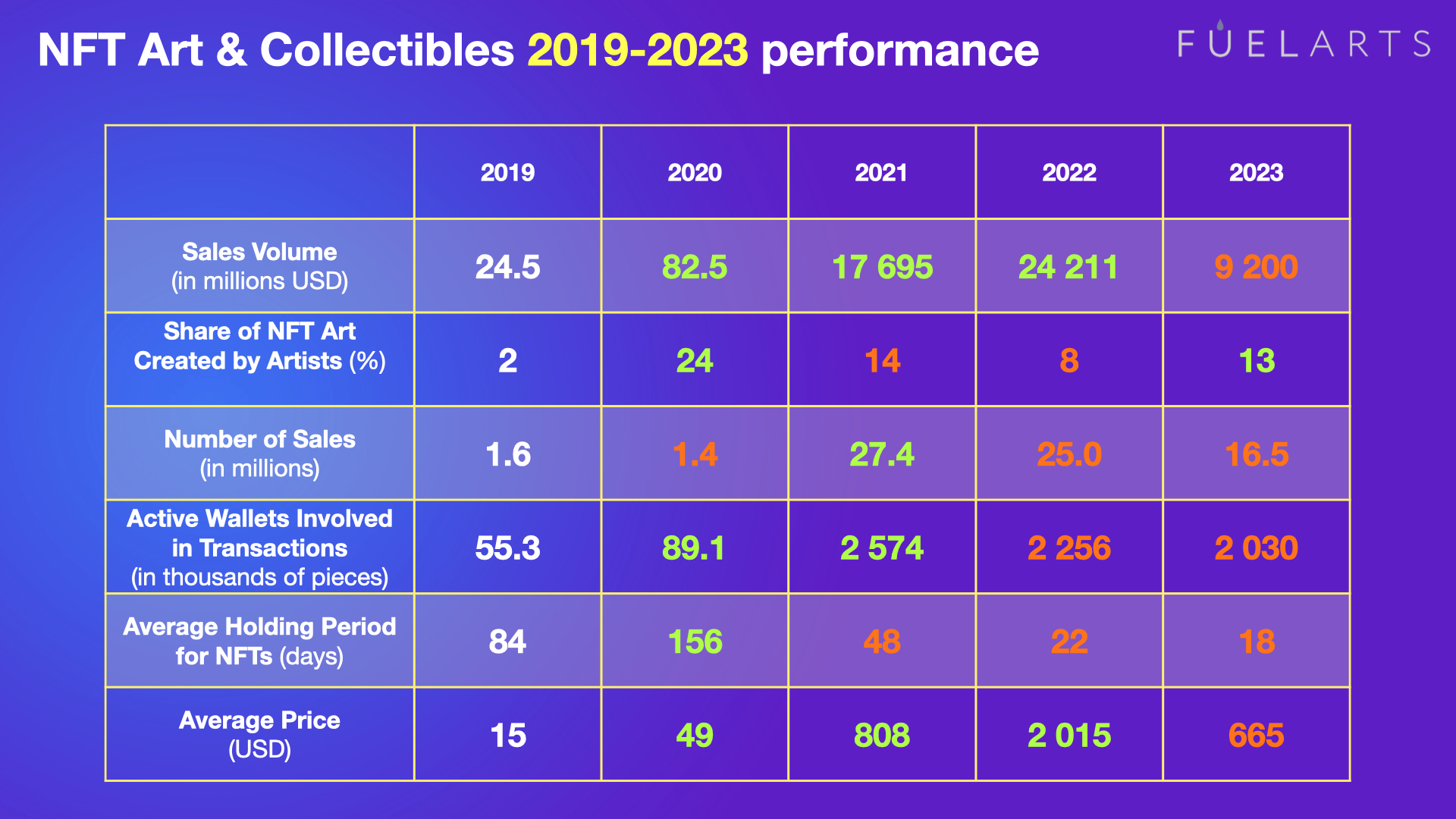

The following data illustrates the NFT market’s key metrics from 2019–2023:

The following data illustrates the NFT market’s key metrics from 2019–2023:

Data sources: Nonfungible.com, NFT18.com, Art Basel & UBS Report 2023, 2024

Key takeaways from this table: the share of digital art, graphic design, and collectibles created by professional artists and subsequently sold as "NFT-art" is minimal, averaging 13% over five years since the market's inception. Fifty-two percent of NFT sales volume comes from the online gaming industry, where items such as swords, artifacts, and potions enhance virtual characters. Since 2021, however, many gamers also consider these images "art."

Key takeaways from this table: the share of digital art, graphic design, and collectibles created by professional artists and subsequently sold as "NFT-art" is minimal, averaging 13% over five years since the market's inception. Fifty-two percent of NFT sales volume comes from the online gaming industry, where items such as swords, artifacts, and potions enhance virtual characters. Since 2021, however, many gamers also consider these images "art."

Noteworthy are the last two rows: the average holding period and average price of NFTs. Holding period influences liquidity and speculation, a factor that has followed the market closely. In 2021, eight out of ten purchased NFTs were immediately listed for resale, while only two were intended for long-term holding (reflecting a loose form of collecting). As we see, holding periods have declined consistently, while average prices, having risen sixteen-fold between 2020 and 2021, dropped threefold between 2022 and 2023.

Let’s return to the end of 2020, the start of the NFT boom. To avoid an extensive historical review, we’ll focus on a few key moments from 2021–2022:

Everything seemed set for NFT’s triumphant rise. Then political events in 2022 led to economic uncertainty, exposing hidden issues within the crypto community...

- Beeple and the Epochal Sale at Christie’s

- Brands Enter the Game

- ArtTactic and Art Basel

- Startups and Ecosystems

Everything seemed set for NFT’s triumphant rise. Then political events in 2022 led to economic uncertainty, exposing hidden issues within the crypto community...